“Prostitution”: A State Affair

From the 19th century onwards, European states have adopted one of three approaches to managing prostitution: the prohibitionist regime, which bans and condemns all parties (prostitutes, clients, and pimps); the regulatory regime, which controls and regulates all activities; and the abolitionist regime, which seeks to eradicate prostitution.

The 19th century: towards a hygienic and moral model

In Belgium, the regulatory regime was introduced in 1844. The regime was supported by the Academy of Medicine and was similar to France and England at the time. This regime remained in force until 1948. The State considered prostitution a “necessary evil,” “inseparable from a male society.” There was no other choice than to “tolerate” it. The authorities regulated and controlled prostitutes in order to exclude them from society, so that they could no longer “contaminate and pervert morality or public health.” They were seen as a necessary part of society, but could not be an active part of it. Prostitutes were therefore “registered,” which means that they were classified by the municipality and regularly visited by doctors. Subjected to regular and sometimes violent medical examinations, they were locked up in a specialized institution if the doctor diagnosed an illness, to undergo compulsory treatment there. In Brussels, “sick” prostitutes were usually sent to the Saint-Pierre Hospital in Uccle, where a ward had been reserved for them since 1818. In comparison, the Saint-Jean Hospital created a gynaecology department reserved exclusively for women who were considered moral, such as mothers and young girls from good families.

Under the regulatory regime, prostitutes had to carry out their activities in brothels approved by the college of mayors and aldermen or out of sight, since they were no longer allowed to circulate in public spaces. They therefore formed a separate, marginalized category that no longer had the same rights as the rest of the population. The regulatory system was a failure. Illegal prostitution increased, brothels fell into crisis due to the rise of fashionable cafés and ballrooms, and syphilis continued to spread. In addition, an internationally known scandal erupted in a Brussels brothel on the Avenue du Paradis.

The scandal of the ‘little English girls’

The scandal of young English prostitutes found in Brussels became the subject of an international press campaign which, under the term “white slave trade”, denounced the activity of kidnapping young girls who were forced to prostitute themselves abroad. This case allowed abolitionist feminists to make their voices heard. On the one hand, Josephine Butler, an English feminist and abolitionist, criticized the sexual double standards that degraded prostitutes. They were stigmatized and subjected to humiliating treatment and controls, while clients and politicians went completely unpunished. On the other hand, the scandal of the “little English girls” was used by the feminists of the time to advance their cause in England and Belgium: they wanted to put these women, whom they considered immoral and childish, on the “right path” without listening to the demands of the prostitutes. The ideas of Butler and her allies spread throughout Europe. In 1949, the Geneva Convention marked a major victory for the abolitionist cause. The text adopted by the UN declared that “prostitution and traffic in human beings are incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person” and opposed all forms of regulation.

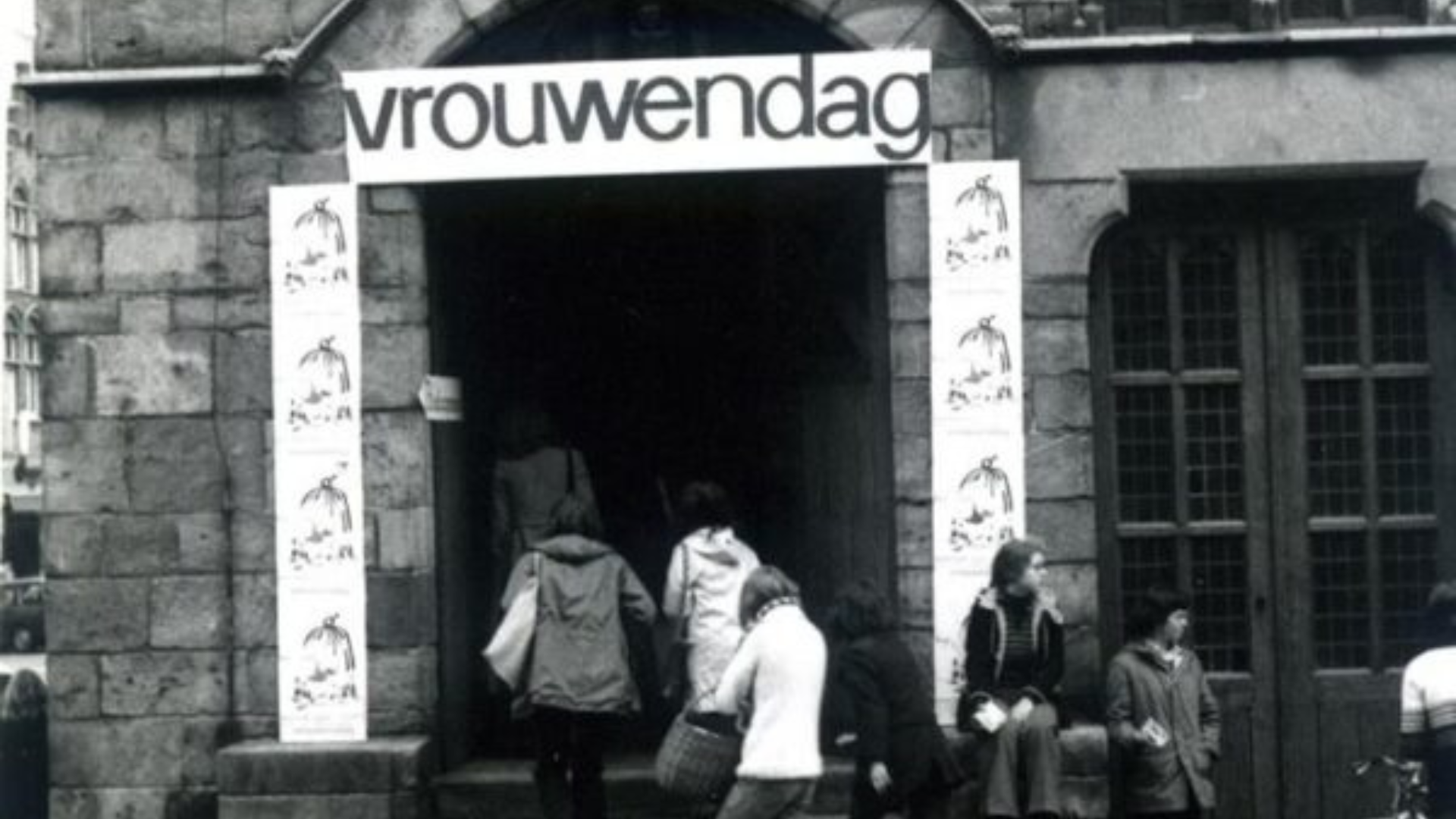

Towards the end of the 20th century: a new identity for sex workers

In 1975, hundreds of prostitutes in Lyon challenged the French state by occupying the church of Saint-Nizier for a week. They denounced police repression, the closure of the hotels where they worked, and the unsolved brutal murders of prostitutes. They received support from feminist activists and could even count on a visit from Simone de Beauvoir. The case was picked up in the press and the international media attention marked a turning point in sex worker organizing.

Today, feminist movements are deeply divided over sex work and prostitution. For abolitionist activists, prostitution undermines the dignity of all women, as bodies are objectified to satisfy male pleasure. Prostitutes are reduced to negotiated and overexploited commodities for the benefit of a capitalist and patriarchal society. To put an end to this situation once and for all, punishing clients and helping prostitutes rebuild their lives would be solutions in line with the struggle of Joséphine Butler in the 19th century (today the Swedish and French model). On the other side of the spectrum, feminists denounce government policies that make sex workers even more precarious, as they face worsening conditions in order to continue working. They denounce the way in which the voices of those most affected are too often ignored (because they are supposedly always manipulated by their pimps and are unable to take action themselves).

According to Juliette Comte (2010), the terms “prostitution” and “prostitute” are strongly associated with crime, debauchery and immorality and are negatively charged with a stigma that characterizes and discredits those who sell sexual services. This is why American sex workers proposed the terms sex work and sex worker in the 1980s. The aim was to reflect that exchanging money for sexual services is work for some, but also to facilitate better social perception and lead to better working conditions”. The union adds that to combat the exploitation of people, “we must encourage the empowerment of sex workers and raise awareness in society for a more respectful welcome of these communities” (source: UTOPSI).

In 2022, the mobilization of sex work activists bore fruit. From that moment on, sex work was no longer included in the Criminal Code: sex workers were thus given the same rights as any other employee. “It was already possible to perform sex work as a self-employed person. Thanks to this law, sex workers will also be able to work on the basis of an employment contract, which will give them access to social security: pensions, unemployment, health insurance, family allowances, annual leave, maternity leave, etc. At the same time, the law guarantees that sex workers are protected against occupational risks in the workplace and imposes conditions on employers” (source: UTOPSI)

The issue of sex work/prostitution continues to divide feminist circles. Therefore, the use of the terms “prostitution” and “sex work” is not unimportant, as each is loaded with symbolism and is now associated with the positions of those who use them, while being rejected by supporters of the other camp. As Gayle Rubin, an American pro-sex work activist and anthropologist, puts it, sexuality is a historically situated social construction of gender. Consequently, prostitution, as a sexual practice, is itself historical and must be questioned in light of its history and cultural context. This new approach would allow us to move away from a polarized and binary pro- or anti-sex vision.

Elisabeth Fiévez

Volunteer at Amazone